Aravalli Hills on Trial

- Sakshi Mishra

- Feb 4

- 8 min read

For millennia, the Aravalli Hills have stood as silent sentinels over northwest India, an ancient geological fortress older even than the Himalayas, stretching from Gujarat through Rajasthan and into Haryana and Delhi, shaping climate, culture, and livelihoods across the region. Far more than a scenic backdrop, the range acts as a barrier against the eastward advance of the Thar Desert, functions as a critical natural groundwater reservoir recharging aquifers for millions, moderates local climate and monsoon behaviour, and sustains biodiversity corridors and rural livelihoods linked to grazing, forest produce, and seasonal water bodies. In legal and constitutional terms, these functions anchor the Aravallis within the framework of ecologically sensitive zones and engage the State’s obligations under Articles 21, 48A, and 51A(g) of the Indian Constitution. Yet, by late 2025, this ancient ecological guardian effectively found itself in the dock, at the centre of a courtroom drama where economic development, political decision-making, and strategic interests were weighed against environmental preservation. A series of policy decisions and development proposals ranging from mining and real estate expansion to highways and strategic infrastructure triggered intense litigation, as petitioners alleged large-scale violations of environmental norms and sought judicial intervention to protect what they framed as a constitutional right to a clean and healthy environment. Before the bench, the Aravallis were translated into the language of law through maps, notifications, and statutory instruments under the Environment (Protection) Act, the Forest (Conservation) Act, the Wildlife (Protection) Act, and various eco-sensitive zone notifications raising core questions: to what extent can development override ecological limits; whether statutory safeguards and the public trust doctrine have been honoured or breached; how the degradation of the range impacts the fundamental right to life under Article 21 through worsened air quality, water insecurity, and climate vulnerability; and how claims of strategic or economic necessity should be balanced against environmental security.

Though not formally granted legal personhood, the hills were argued to be an ecological entity whose continued degradation would have direct and irreversible consequences for present and future generations, invoking principles of precaution, intergenerational equity, and polluter pays. In this way, the 2025 Aravalli litigation became a test case for India’s environmental jurisprudence: could the country pursue growth while preserving a mountain range that underpins the ecological survival of millions in the National Capital Region and beyond? The outcome of this legal battle would not be measured only in judicial orders or policy amendments but in the lived reality of the region—the air breathed in Delhi and Gurgaon, the depth of wells in Rajasthan and Haryana, the persistence of wildlife in shrinking habitats. As arguments continued to echo through courtrooms, the Aravalli Hills emerged not merely as a line on the map, but as a legal battleground and ecological lifeline, against which India’s commitment to its constitutional promise of environmental protection would be judged for decades to come.The Aravalli range, among the oldest fold mountains in the world with an estimated age of over 3 billion years, has long been recognised not only for its geological significance but also for its crucial ecological role. Stretching across parts of Haryana and Rajasthan, these hills support dry and thorn forests, sustain critical wetlands such as Sambhar Lake, and provide vital habitats for wildlife, including tiger territories in protected areas like the Sariska Tiger Reserve.

For decades, a web of environmental laws, forest notifications issued in 1992, and judicial interventions by the Supreme Court and the National Green Tribunal (NGT) sought to shield the Aravallis from relentless mining, illegal construction, and large-scale destruction of vegetation. These legal safeguards, widely reported in outlets such as The Wire and Aaj Tak, were intended to establish clear limits on extractive and construction activities in ecologically sensitive zones.

The year 2025 marked a significant turning point in this ongoing legal and ecological saga. Multiple cases and petitions brought the Aravallis back into the spotlight, with the NGT demanding strict accountability from officials in Haryana and Rajasthan over illegal mining operations that appeared to violate the 1992 Aravalli notifications. Investigative reports, including those by Down to Earth, highlighted how large tracts of the hills continued to be degraded despite the regulatory framework ostensibly in place.

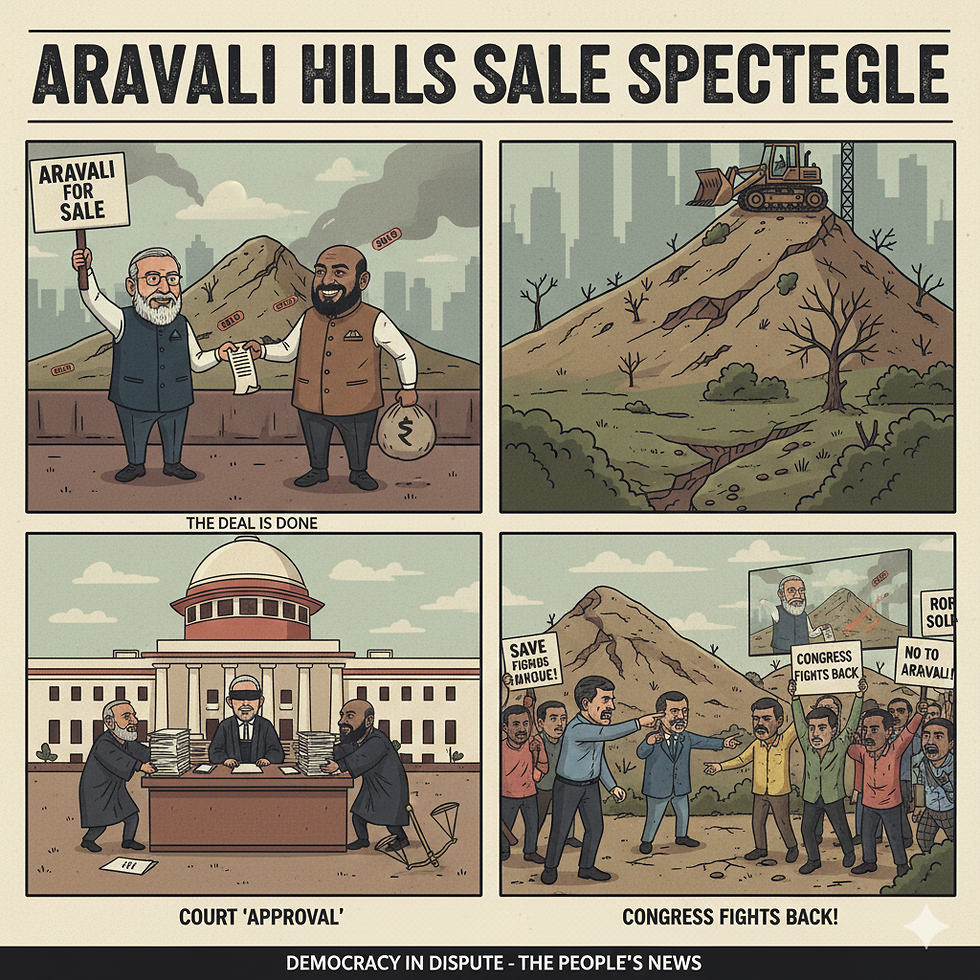

Courtrooms increasingly became the arena where the future of the Aravallis was contested. Judicial benches repeatedly grappled with a central question: could land records, building permits, and environmental clearances obtained under various state procedures override, dilute, or sidestep the overarching principles of ecological protection embedded in national environmental law? Coverage in publications such as Jagran captured this tension, as arguments from government departments, private entities, and environmental petitioners clashed over interpretations of legality and public interest.

Each case read like testimony in a larger, ongoing trial development claims set against the imperatives of environmental conservation. In this unfolding legal narrative, the Aravallis themselves stand as both victim and witness, their fate hinging on how courts, regulators, and governments choose to interpret and enforce the law in the face of mounting ecological crisis and contested development priorities. On 20 November 2025, the Supreme Court of India accepted a new, highly contested definition of what legally constitutes the “Aravalli Hills and Ranges.” Acting on a government-backed proposal, the Court endorsed a criterion under which only landforms that rise at least 100 metres above the surrounding local terrain would be recognised as part of the Aravallis. As reported by The Wire, this ostensibly technical and scientific standard has far-reaching legal and ecological implications, effectively redrawing the boundaries of what is protected as the Aravalli landscape.

Government reports and internal assessments reviewed in the public domain indicate that more than 90% of the historic Aravalli expanse would fall outside the ambit of protection under this new height-based definition, simply because these formations do not meet the 100-metre cutoff. According to coverage in The Wire, this reclassification strips legal safeguards from vast stretches of hills and ridges that have long been understood scientifically, culturally, and administratively as part of the Aravalli system. The situation is particularly acute in Rajasthan, which hosts the largest share of the range: data reported by The Times of India suggest that only about 8.7% of the state’s Aravalli hills now qualify under the revised standard, exposing extensive tracts to intensified mining, construction, and other extractive activities.

The decision has triggered sharp reactions from environmentalists, civil society groups, and political leaders. Many have characterised the judgment as a de facto green signal for the dismantling of one of India’s most critical ecological barriers. The New Indian Express reports that Congress leader Sonia Gandhi went so far as to describe the ruling as a “death warrant” for the Aravallis, warning that the new definition effectively dismantles long-standing protections and opens the door to accelerated ecological degradation. Activists argue that the height criterion is arbitrary from an ecological standpoint, bearing little relation to the functions that these hills perform in terms of climate resilience, biodiversity support, and hydrology.

Public response has been swift and visible. Across Gurugram, Delhi, and multiple districts in Rajasthan, as well as in digital spaces, citizens have taken to the streets and online platforms to express their alarm. Campaigns led by groups such as People For Aravallis and Save Sariska, documented by The Wire, have mobilised schoolchildren, resident welfare associations, village communities, and urban professionals in coordinated protests, marches, and awareness drives. For many participants, this is not merely a battle over forest cover, but a fight for breathable air, secure water supplies, and the long-term climate resilience of the region.

At the heart of activists’ objections lies a fundamental ecological argument: lower-elevation hills, even those under the 100-metre threshold, play an indispensable role in the broader landscape. As highlighted by The Times of India, these formations function as natural windbreaks that help reduce the movement of dust and sand from the Thar Desert into the Indo-Gangetic plains and the Delhi-NCR region, thereby mitigating air pollution and dust storms. Environmental experts further warn, in reports including those from India News, that once these areas lose their protected status, diverse ecosystems comprising scrub forests, grasslands, and wildlife habitats are likely to be opened up for mining leases, real estate projects, and industrial corridors.

The ecological risks are not confined to air quality and habitat loss. Analysts cited by The Times of India emphasise that key groundwater recharge zones and biodiversity corridors are embedded within these lower and mid-height hills. Fragmenting or flattening them for commercial use could severely reduce natural groundwater replenishment, disrupt wildlife movement, and intensify the region’s existing water stress. Critics contend that the judgment privileges a narrow, topographic reading of “hills” over a holistic understanding of ecological function and landscape integrity.

In response, a wave of petitions, representations, and open letters has been directed to constitutional and statutory authorities, including the Supreme Court itself. As reported by The Wire, these communications call for the recall or reconsideration of the controversial judgment and urge that the Aravalli range be notified as a Critical Ecological Zone. Such a designation, proponents argue, would embed in law a clear hierarchy of values, explicitly requiring that long-term ecological security, public health, and intergenerational equity take precedence over short-term economic gains from mining, construction, and industrial expansion.

As the legal and civic debate intensifies, the fate of the Aravallis now hinges on whether Indian jurisprudence will interpret environmental protection as a central, non-negotiable component of the right to life, or allow technical definitions and narrow economic logics to determine the contours of one of the subcontinent’s oldest and most important mountain systems. Even as the Supreme Court endorsed the controversial new definition of the Aravalli Hills, the Bench attempted to temper its impact by placing clear brakes on mining and extracting activities in the region. According to the Universal School of Administration, the Court has barred the issuance of any new mining leases in the Aravalli belt until the government formulates a comprehensive, scientific and sustainable mining plan. At the same time, as reported by NDTV India, existing mining operations are allowed to continue only under stringent environmental safeguards, with a categorical direction that no final or expanded licences may be granted without scrutiny and oversight by the central authorities. This calibrated approach reveals a familiar judicial tightrope walk: affirming the principle of conservation and recognising the Aravallis as a critical public good, while still permitting development and resource extraction, albeit under tighter, court-mandated constraints and regulatory supervision. In this high-stakes courtroom where law and ecology intersect, every petition filed, every definition adopted, every protest staged, and every judgment delivered is contributing to a growing evidentiary record, one that India will ultimately adjudicate not only through its courts but through its politics, environmental policy, and collective conscience. The Aravalli Hills, older than the Himalayas and indispensable to the survival and well-being of millions, now stand at the centre of what amounts to a national forensic audit of the country’s legal and developmental priorities.

At stake is far more than a technical interpretation of what qualifies as a “hill” or a “range.” The question before the Nation is whether the law will operate as a shield for nature’s legacy or as an instrument to redraw and dilute that legacy until it slips beyond the reach of protection, surviving only in maps, memories, and archival records. As the Aravallis are subjected to this unprecedented legal and political scrutiny, the outcome will set a defining precedent: will India’s environmental jurisprudence affirm ecological integrity as a non-negotiable public trust, or will it permit nature to be redefined, incrementally and invisibly, until it disappears from the law even as its absence is felt in our air, our water, our climate, and in the texture of daily life?

Comments